In 1890, Galveston finally received what it needed to become an economically competitive port: a 6.2 million dollar congressional appropriation to deepen the harbor. News of the appropriation sent Galveston into a flurry of spontaneous celebrations and a rush to plan six months’ worth of festivities called the Deep Water Jubilee.

In 1890, Galveston finally received what it needed to become an economically competitive port: a 6.2 million dollar congressional appropriation to deepen the harbor. News of the appropriation sent Galveston into a flurry of spontaneous celebrations and a rush to plan six months’ worth of festivities called the Deep Water Jubilee.

Galveston did not successfully lobby congress alone. By working with other western cities and interests, they proved together that deep water at Galveston held national importance. As the farthest port with access to the Atlantic trade, Galveston and the West stood to gain handsomely from increased goods traveling through the harbor. Deep water meant larger ships carrying more cargo, making more money for the western states.

After over twenty years of planning, deep water was within Galveston’s reach. With banquets, oyster roasts, and maritime excursions, Galveston set about thanking its many partners in November of 1890. In February, Galveston held one of her famous Mardi Gras events accompanied by a trades display parade. In April, Galveston hosted the biennial Saengerfest, which boasted three days of concerts by German music groups from across the state. The Deep Water Jubilee ended with the arrival of sitting President, Benjamin Harrison, who signed the bill into law, and all the pomp and circumstance befitting a presidential visit.

Problems with Galveston’s Harbor

In 1852, a United States survey named Galveston as the best natural harbor on the Texas Coast despite a major problem: two sandbars blocked the entrance to the port. At low tide, there was only 9½ feet of water over the inner bar and 12 feet over the outer bar, forcing large vessels and their lucrative cargos to anchor outside the sandbars. Galveston needed deeper water.

Slow Attempts and Small Improvements

They measured about six feet long and six feet tall. Courtesy of Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas

In 1870, the US Army Corps of Engineers started a 27-year project to dredge the inner channel and build jetties. On the first attempt, Congress granted $25,000 to extend the wooden pile jetty from the eastern end of the island. After three years of work, the pile jetty only deepened the harbor 2 ½ feet. While an improvement, Galveston still needed deeper water.

In 1874, Captain C.W. Howell took over the project and suggested using gabions (cylindrical, wicker cages filled with sand) to construct the jetties. Unfortunately, after another three years, a hurricane damaged the newly finished gabionade revealing that the method was ineffective.

Major Samuel M. Mansfield assumed control of the project in 1880. The deep water improvements crept along slowly, drawing harsh criticism. Impatient, the public urged the city to take control and hire their own engineer. In 1883, Galveston’s mayor established the Deep Water Committee, comprised of prominent, local businessmen. They hired James Eads, an Indiana native with a proven engineering record. Galveston asked the federal government to fund Eads’ plan, but Congress demanded that the Corps remain as leaders of the project with Eads working as only a contractor. Offended, Eads withdrew his proposal.

ELISSA docks at Galveston

As construction crept forward and tensions between the city and the Corps rose, ships with higher and higher drafts docked at Galveston. The newspaper published Eads’s thoughts on the deep water project on December 28, 1883, in the same issue that advertised 1877 Tall Ship ELISSA’s arrival with a cargo of bananas. Were it not for the early jetty attempts, ELISSA, drawing 14 feet of water when fully laden, could not have docked at Galveston.

As construction crept forward and tensions between the city and the Corps rose, ships with higher and higher drafts docked at Galveston. The newspaper published Eads’s thoughts on the deep water project on December 28, 1883, in the same issue that advertised 1877 Tall Ship ELISSA’s arrival with a cargo of bananas. Were it not for the early jetty attempts, ELISSA, drawing 14 feet of water when fully laden, could not have docked at Galveston.

Political Sandbars

The struggle to carve a deep channel through two sandbars mirrored the political difficulty of passing the Rivers and Harbors Act, which provided funding for the project, through two houses of Congress. As the bill moved through special committees, the House of Representatives and the Senate, it diminished in amount or was struck down completely. By the time Congress approved the bill, the meager funds were not enough to carry the project forward. In 1883, Galveston believed that unless Congress budgeted sufficient money for deep water, she could not become a competitive port.

“The plan, for aught I know, may be a good one, and Colonel Mansfield is doubtless a good engineer. My objection is to the restricted method of the government dispensation of funds” – A Concerned Citizen, 1883

Rallying the Western States

In response, the Deep Water Committee, headed by William L. Moody, changed its strategy to make Galveston’s harbor a national issue rather than just a local problem. To do this, they enlisted help from western states who desperately wanted a closer port.

During three Interstate Deep Water Conventions, Galveston united the western states. The Convention elected a man named Walter Gresham from Galveston as chairman of the delegation. Gresham moved from Virginia to Texas after the Civil War, opening a law practice in Galveston. He was an active stockholder in the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe railroad and served in the Texas legislature from 1887 to 1891.

Under Gresham’s leadership, the group decided that one member from each state and territory would form a delegation to lobby Congress. Naturally, Gresham represented Texas interests, making frequent trips to Washington D.C. and shepherding the bill behind the scenes.

Deep Water At Last

In 1890, a US Army Corps of Engineers survey announced Galveston as the best Texas harbor due to its location, size and railroad facilities. They estimated that 30 feet of water could be obtained over the sandbars for a cost of $6.2 million dollars. With this powerful support and the endorsement of the western state delegates, Galveston finally had a fighting chance.

The Rivers and Harbors bill passed the House of Representatives on Saturday, September 6th, 1890 and the Senate two days later. President Benjamin Harrison immediately signed the bill making it a law. Work began in August of 1891 using pink granite from the recently discovered quarry in Marble Falls, Texas while the vessel GEN. C.B. COMSTOCK dredged the channel. By 1897, the finished jetties created 26 feet of water over the outer bar. Cotton exportation jumped from 22% to 64% as the city welcomed larger cargo ships. At last, Galveston had her deep water port.

Galvestonians Go Wild

On September 19th, 1890, news that Harrison signed the Rivers and Harbors Act reached the city of Galveston in a telegraph from Walter Gresham that read, “The bill with provision for making a first-class harbor at Galveston has become law.” After over twenty years of waiting and disappointment, Galveston burst into a gleeful celebration.

On September 19th, 1890, news that Harrison signed the Rivers and Harbors Act reached the city of Galveston in a telegraph from Walter Gresham that read, “The bill with provision for making a first-class harbor at Galveston has become law.” After over twenty years of waiting and disappointment, Galveston burst into a gleeful celebration.

Locomotives, ships, and mills all blew their steam whistles, sounding a deafening chorus. Businessmen threw their hats in the air, shooting fireworks and reveling in the streets. Citizens flocked downtown to celebrate with one another while an improvised brass band paraded through the city to shouts of “Hurrah for Galveston and deep water!” Mayor Fulton issued an immediate proclamation authorizing the use of cannons, guns, firecrackers and whistles, setting aside the next day as a holiday so that the whole city could celebrate.

A Spontaneous Holiday

All of Galveston thronged noisily through the streets setting off firecrackers and beating drums. Churches rang their bells and businesses draped decorative bunting on their storefronts. Visitors from Houston, Austin and Dallas, invited by telegraph message, arrived at sunset for a torch-lit parade down 23rd Street. An estimated 15,000 people gathered to hear speeches at the Beach Hotel after the parade.

All of Galveston thronged noisily through the streets setting off firecrackers and beating drums. Churches rang their bells and businesses draped decorative bunting on their storefronts. Visitors from Houston, Austin and Dallas, invited by telegraph message, arrived at sunset for a torch-lit parade down 23rd Street. An estimated 15,000 people gathered to hear speeches at the Beach Hotel after the parade.

“The rich and poor nudged and pushed each other for points of outlook; the aged and the young forced their way through the surging mass, and the matron and maid elbowed… All Galveston seemed to have concentrated in one locality” Galveston Daily News

Deep Water Jubilee Committee

Four days later, the Mayor appointed a new committee of twenty-five businessmen, who assembled quickly to plan the Jubilee. They announced that Galveston would host three events to keep the city buzzing for six months: a November celebration for special guests, a Trades Display and Mardi Gras in February, and a Saengerfest in April.

“Galveston can advertise herself with immense results by giving the grandest demonstration that Texas or the Southwest has ever seen.”

William H. Sinclair served as chairman of the committee, which was only natural considering his reputation as Galveston’s greatest advocate capable of accomplishing lofty goals. Sinclair could always get things done. He settled in Galveston by the 1870s and quickly rose to prominence becoming president of the Galveston City Railroad Company, financing the development of the Beach Hotel and serving as Postmaster. When asked if he was too busy to be chairman he replied, “Not at all, I have always time to devote to any movement which promises so much for Galveston.”

“Galveston never does anything halfway”

Although the Jubilee Committee expected Mardi Gras and Saengerfest to draw large crowds, they wanted to thank distinguished guests and partners from the western states separately. With no time to waste, they planned a celebration for November 18th and 19th with public events and an exclusive banquet. Visitors crowded aboard Galveston-bound trains and arrived to a full schedule of events:

Although the Jubilee Committee expected Mardi Gras and Saengerfest to draw large crowds, they wanted to thank distinguished guests and partners from the western states separately. With no time to waste, they planned a celebration for November 18th and 19th with public events and an exclusive banquet. Visitors crowded aboard Galveston-bound trains and arrived to a full schedule of events:

Tuesday, November 18th, 1890

10am: Excursion to the Jetties: Over 700 people piled onto the S.S. COMAL, a Mallory shipping vessel, for an excursion to the jetties. The COMAL traveled to the outer bar while a band played and jubilee ambassadors answered questions about the jetty work.

2pm: Oyster Roast: Visitors traveled down 23rd street to Beach Park, the baseball field and grandstands, where Galveston roasted 100 barrels of oysters for her guests. After everyone ate their fill, the committee crowned ex-Texas Governor, Francis Lubbock as “champion oyster eater” to cheers and laughter from the crowd. Crowning a champion was a light-hearted tradition in Galveston meant in good fun to embarrass an important guest and to allow them to give a speech.

8pm: Evening Reception: Guests gathered at the Garten Verein on Avenue O for music and refreshments. The main attraction was dancing in the pavilion, which still stands today, but many played tenpin, a form of bowling, on the lush grounds.

Wednesday, November 19th, 1890

9am: Excursion to the Jetties: On the first day, nearly 800 people were left waiting on the docks unable to fit aboard, so the Jubilee Committee arranged a second excursion on Wednesday.

2 and 4 pm: Parades: More trains brought visitors bringing the total to around 7,000. Guests and Galvestonians alike thronged the streets until 23rd was one “dense mass of seething humanity.” The first parade started downtown and included marching bands, military groups, the mounted police, fire department, and civic organizations. The second, a military dress parade, took place along the beach.

8pm: Fireworks on the Beach: The fireworks were the only disappointment. Crowds gathered along the beach at 6:30, but by 9:00 they were still waiting. Scarcely had the display begun when an accidental fire ignited the stack, shooting them all off at once and frightening the crowd.

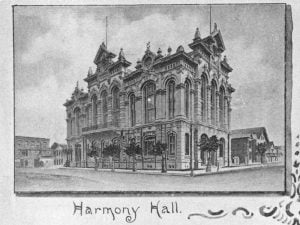

8pm: Banquet at Harmony Hall: Galveston welcomed 300 invited guests to Harmony Hall for a lavish banquet. A committee of prominent women transformed the second floor into an island oasis, filling every corner with tropical plants, ferns, palms, and flowers. They arranged the tables to look like the island and her jetties, with a fifty by twenty-foot table representing Galveston. The guests, men only, feasted on oysters, turtles, beef filet, quail, shrimp, vegetables and dessert while toasting their success with wine and champagne.

A Tradition Renewed

Although Mardi Gras was first celebrated in a private home on the island in 1856, city-wide festivities for the public started in 1871. By 1885, the carnival celebrations shrunk in size and the next year passed with only private parties to mark the occasion. For Galveston’s Jubilee, the committee envisioned attracting visitors to the city by reviving “old-time Mardi Gras processions” harkening back to its former glory, combined with a trades display.

Although Mardi Gras was first celebrated in a private home on the island in 1856, city-wide festivities for the public started in 1871. By 1885, the carnival celebrations shrunk in size and the next year passed with only private parties to mark the occasion. For Galveston’s Jubilee, the committee envisioned attracting visitors to the city by reviving “old-time Mardi Gras processions” harkening back to its former glory, combined with a trades display.

Arrival of King Momus

Momus, King of Mardi Gras, arrived with much fanfare on Saturday evening, February 7th. His royal barge docked in the harbor and participants paraded down 23rd Street in decorated carriages. Accompanied by torches and fireworks, the procession magically glowed as it moved through the streets to the Beach Hotel.

Trades Display

On Monday, the Jubilee hosted a trades display of decorated wagons advertising the “riches, resources, and wonders” of Galveston and the State of Texas.

On Monday, the Jubilee hosted a trades display of decorated wagons advertising the “riches, resources, and wonders” of Galveston and the State of Texas.

Unfortunately, a cold north wind blew into the city bringing low temperatures and strong gusts. Despite blowing apart two wagons, the crowds still packed the streets to see fifty-two wagons parading through Galveston.

The wagons advertised a range of businesses including art suppliers, bakers, importers, grocers, piano makers, vinegar and pickle canners, roofers, and representatives from every aspect of the cotton industry. McKinney, Moore and Company created the most elaborate display, transforming their wagon into a 25 foot fully rigged ship announcing deep water in Galveston. The crowd’s favorite wagon was made by Freiberg, Klein and Company, a liquor and cigar dealer, whose wagon resembled a beer barrel. They handed out free beer to spectators along the parade route.

Celebrating the Great West

Unlike the day before, the sun on Tuesday, February 10th shone brightly, warming the island. Crowds once again packed the streets for a Mardi Gras parade of seventeen specially created floats. First came King Momus enthroned on purple and golden clouds, followed by Galveston, Queen of the Sea, portrayed by Sallie Trueheart. She sat in a jewel-encrusted, shell-shaped chariot pulled by glittering dolphins. These were followed by floats representing each western state that benefitted from Galveston’s deep water harbor. The final float depicted the United States complete with a capital dome, Lady Liberty and firing cannons.

Unlike the day before, the sun on Tuesday, February 10th shone brightly, warming the island. Crowds once again packed the streets for a Mardi Gras parade of seventeen specially created floats. First came King Momus enthroned on purple and golden clouds, followed by Galveston, Queen of the Sea, portrayed by Sallie Trueheart. She sat in a jewel-encrusted, shell-shaped chariot pulled by glittering dolphins. These were followed by floats representing each western state that benefitted from Galveston’s deep water harbor. The final float depicted the United States complete with a capital dome, Lady Liberty and firing cannons.

After the parade, over 4,000 people attended the Mardi Gras ball. Since there was no venue large enough to hold the crowd, the committee hosted two balls at the same time: one at Harmony Hall and one at the Cotton Exchange. At eleven o’clock, Momus arrived first at Harmony Hall for a ceremony presenting his royal court. He and Queen Trueheart opened the dance floor before a carriage whisked the court away to the Cotton Exchange where they repeated the ceremony. At both venues, there was a waltz only for those guests wearing masks followed by dancing long into the night.

Saengerfest Joins the Jubilee Saengerfest, literally translating as “singer festival,” was a state-wide series of concerts by German singing groups. At the end of the 17th Saengerfest held in Austin, the association selected Galveston to host the next biennial event in 1891, electing Julius Runge as President of the executive committee.

When the committee started planning the Jubilee in September, they considered Saengerfest, which was already on the books for April, as the anchor event. Even if the November celebration and Mardi Gras were unsuccessful, they could at least count on three to six thousand visitors for Saengerfest. With Julius Runge also serving on the Jubilee committee, cooperation between the two groups ran smoothly.

To fund the concerts, managers sold Saengerfest shares at $10 apiece, rewarding purchasers with two free tickets per concert. Unfortunately, by February 1891, they had not sold many shares since Galveston citizens had already donated liberally to other Jubilee events. To encourage sales, a local choir hosted a concert to inspire Galveston. It worked. The concert peaked Galveston’s appetite for musical programs and spurred fundraising.

Saengerfest Hall

Expecting to host 3000 people at each performance, Galveston needed a bigger concert hall. The committee converted the old Taylor Cotton Compress yard at 31st and Market Street into an auditorium. Noted architect, Alfred Muller, chaired the Committee on Building and Decoration to oversee its redesign. The interior was hardly recognizable as a warehouse by the time he finished. It seated 2,400 people with extra standing room and opera boxes, a shell-shaped ceiling to help acoustics, and a stage on the west end capable of holding 500 singers. Decorators draped the hall with bunting, evergreen boughs, flags, and portraits of well-known German composers.

Three Days of Concerts

Seventeen different singing societies, performed during Saengerfest. During the day, the visiting singers toured the city, feasted on oysters, drank beer, took boat excursions, and banqueted. In the evening, thousands packed into Saengerfest Hall to listen to the sweet melodies of Mozart, Mendelssohn, Wagner, and Schumann.

Seventeen different singing societies, performed during Saengerfest. During the day, the visiting singers toured the city, feasted on oysters, drank beer, took boat excursions, and banqueted. In the evening, thousands packed into Saengerfest Hall to listen to the sweet melodies of Mozart, Mendelssohn, Wagner, and Schumann.

The program featured overtures by a forty-three person orchestra, songs by the individual singing societies, and solo pieces. Mrs. Mayo Rhodes from St. Louis received top billing as the most polished and practiced soloist, but a young woman named Emmy Gareissen received a special notice and a “storm of applause” for her rich alto voice. After the Saengerfest, twenty-year-old Gareissen toured Germany to much success. Soon after, she married a fellow voice teacher and they moved to Michigan where she continued singing and taught music lessons.

In April 1891, President Benjamin Harrison, who signed the Rivers and Harbors Act, set out on a railway tour across the United States. For the final celebration of the Deep Water Jubilee, Galveston invited President Harrison to visit the city on his tour. He accepted, sending Galveston into a flurry of preparation.

Saturday, April 18th: The President’s Arrival

Members of the official reception committee boarded a special train to meet Harrison in Houston and escort him to the island. A small group of Galvestonians, including Julius Runge, William, and Caroline Ladd, and George Sealy, spent the hour and seventeen-minute trip with the presidential party exchanging pleasantries and introductions. During the intimate train ride, the Ladd’s son, six-year-old William Jr., presented the President with his first bouquet of flowers on behalf of the island city.

Members of the official reception committee boarded a special train to meet Harrison in Houston and escort him to the island. A small group of Galvestonians, including Julius Runge, William, and Caroline Ladd, and George Sealy, spent the hour and seventeen-minute trip with the presidential party exchanging pleasantries and introductions. During the intimate train ride, the Ladd’s son, six-year-old William Jr., presented the President with his first bouquet of flowers on behalf of the island city.

Immediately after arriving in Galveston, the group boarded the steamer Lampasas with over one hundred invited guests so that Harrison could inspect the jetty works. Among the passengers was the first African American Collector of Customs, Norris Wright Cuney, who Harrison appointed in 1889. Cuney’s work as a political activist gave him something in common with Harrison, who personally endorsed two bills designed to protect African Americans’ right to vote.

Upon returning to the docks, the group piled into carriages for a parade to the Beach Hotel, where the President was staying. The crowd packed the sidewalks, balconies, and second-floor windows along the route. School kids lined the street armed with flowers. The enthusiastic children rained flowers down on President Harrison, hitting him in the face and blanketing him with roses until he was forced with a smile to protect himself with his hat.

Once at the Beach Hotel’s grandstand, Harrison gave the longest speech of his trip, encouraging maritime commerce and the role of Galveston’s harbor in that expansion. Afterward, he patiently spent an hour shaking hands with the excited citizens before retreating to his hotel room.

Sunday, April 19th: A Day of Rest

A religious man, President Harrison requested a light schedule for Sunday to attend church services and rest. Harrison visited First Presbyterian Church where the Mendelsohn’s choir performed the Jubilation Amen, which had been so successful at the Saengerfest. He and his wife took an afternoon walk around Galveston, admiring the handsome homes and gardens along 23rd Street before attending evening services at Trinity Episcopal Church. That night on his way to the train depot, the presidential party stopped at the home of George and Magnolia Sealy for a short visit and glass of wine. Their house, called Open Gates, is still located at 25th and Broadway and was the only private residence that the President visited in Texas. At midnight, Harrison left for San Antonio. His departure marked a proud end to Galveston’s Deep Water Jubilee.

A religious man, President Harrison requested a light schedule for Sunday to attend church services and rest. Harrison visited First Presbyterian Church where the Mendelsohn’s choir performed the Jubilation Amen, which had been so successful at the Saengerfest. He and his wife took an afternoon walk around Galveston, admiring the handsome homes and gardens along 23rd Street before attending evening services at Trinity Episcopal Church. That night on his way to the train depot, the presidential party stopped at the home of George and Magnolia Sealy for a short visit and glass of wine. Their house, called Open Gates, is still located at 25th and Broadway and was the only private residence that the President visited in Texas. At midnight, Harrison left for San Antonio. His departure marked a proud end to Galveston’s Deep Water Jubilee.

Galveston in 1890-1891

Galveston was the third-largest city in Texas (behind Dallas and San Antonio) with a population of 29,084 people. The island city enjoyed many modern conveniences. Houses were lit with a combination of gas and electric lighting and had indoor plumbing. Many families and downtown offices owned telephones, which had been introduced to Galveston in 1879. Although there were no automobiles yet, to get around the city, Galvestonians rode an ever-growing network of electric streetcars. In 1890, a training school for nurses welcomed their first students and the next year the first public medical school in Texas opened, renamed later as the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Galveston was the third-largest city in Texas (behind Dallas and San Antonio) with a population of 29,084 people. The island city enjoyed many modern conveniences. Houses were lit with a combination of gas and electric lighting and had indoor plumbing. Many families and downtown offices owned telephones, which had been introduced to Galveston in 1879. Although there were no automobiles yet, to get around the city, Galvestonians rode an ever-growing network of electric streetcars. In 1890, a training school for nurses welcomed their first students and the next year the first public medical school in Texas opened, renamed later as the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Fashion

The late 19th century saw a growing number of ready-made clothes available for purchase by catalog or in stores. Women’s fashion transitioned from the bustle to the hourglass silhouette and simplified designs. Men wore short hair, pointed beards, and full mustaches and welcomed the bowtie’s return to fashion.

Entertainment

Although both board games and bicycles existed prior to 1890, their popularity peaked during the decade. The sentimental waltz, or romantic

ballad, dominated the music scene as the familiar tempo was easy to dance to and people enjoyed the emotional, grandiose lyrics. As photography advanced, a peculiar pose trended in 1890 where women sat with their backs to the camera, coyly peeking over their shoulder.

Decorative Arts

The 1890s married organic, curving shapes and strong geometric forms in the new style termed, Art Nouveau. Its simplified modern look sharply contrasted earlier intricate designs.

Architecture

Galveston’s architecture in the 1890s drew inspiration from other Midwestern cities and began moving from wood frame construction to more varied masonry materials. Noted architects like Nicholas Clayton and Alfred Muller reveled in the opulent Victorian-style; however, the 1890s also marked a transition to a more restrained and refined aesthetic from the East Coast.

Food

The late Victorian period featured lavish multi-course formal dinners and complicated etiquette. People preferred commercially processed foods over homemade items such as Fig Newtons, invented in 1891, or Cracker Jacks, introduced in 1893. Peanut butter was first developed as a health food in 1890 with its process officially patented in 1895.

ABOUT GALVESTON HISTORICAL FOUNDATION

Galveston Historical Foundation (GHF) was formed as the Galveston Historical Society in 1871 and merged with a new organization formed in 1954 as a non-profit entity devoted to historic preservation and history in Galveston County. Over the last seventy years, GHF has expanded its mission to encompass community redevelopment, historic preservation advocacy, maritime preservation, museum development, and heritage tourism. GHF embraces a broader vision of history and architecture that encompasses advancements in environmental and natural sciences and their intersection with historic buildings and coastal life, and continues to lead on local, state, and national levels with research-driven programs that build awareness of preservation’s role in cultural identity and stewardship across generations.